“TripAdvisor is to travel reviews what Kleenex is to tissues.”

– Henry Harteveldt, Forrester

TripAdvisor may be one of the most fascinating companies I know and so I was excited to dig into their business model as part of my series on scaling. This is a company that took $4 million of invested capital to build a company now worth over $4 billion.

As I mentioned in my post last week, scaling is hard. Really hard. As we have seen with the recent speed bumps at highfliers like Groupon and Zynga, taking “lean startups” from foundation to creating sustainable, scalable, profitable business models is a very rare and special task. That’s why I embarked on this series: to highlight a few companies outside of the Google/Amazon/Facebook pantheon that have built large, sustainable, profitable business models at scale.

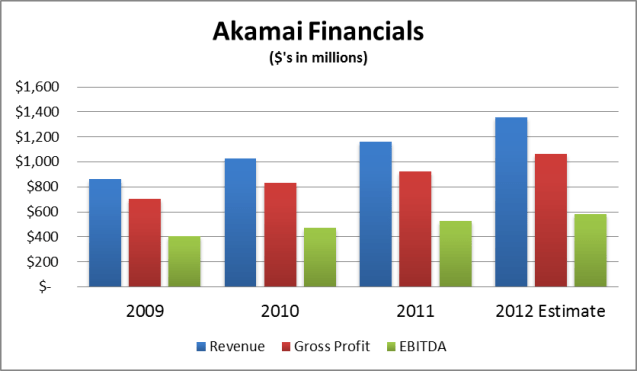

Last week, I wrote about Akamai, a company with strong network effects that successfully transitioned from a single product to build a platform that garners over a billion dollars in revenue and is now a core part of the Internet’s fabric. TripAdvisor is more of a classic consumer Internet success story, but with even more powerful network effects and an amazing business model. Magical, really.

TripAdvisor’s History: Two Big Pivots

Founded in 2000 by Stephen Kaufer and Langley Steinert, Boston-based TripAdvisor is a travel website that provides reviews and other information for consumers about travel destinations around the world. The company is now pervasive – with 65 million unique visitors each month scouring the site for reviews of hotels, restaurants and sites around the globe. I remember last year settling into the booth of a café deep in the rainforest in Costa Rica and looking up to see a placard on the table begging for a positive TripAdvisor review.

Chatting with CEO and cofounder Kaufer this week, I was reminded of the fact that the company started with a very different business model in mind. I first met Steve when he was VP of Engineering at Centerline software, a software development tools startup, and I was a junior in college. He was a fellow Harvard computer science graduate and I was looking for a summer job in software development and found him through an alumni directory. In founding TripAdvisor, Kaufer wanted to take his hard core engineering skills and apply them to vertical search in travel. That is, build a massive database of travel information that provided a white label search engine for travel sites like Expedia and Travelocity. Big Data meets travel…in 2000.

Kaufer described to me with some chagrin what happened – after a year and a half, he had no clients and no revenue and was running out of money. Then, 9/11 hit and the travel industry was decimated. Kaufer began to despair that his fledging start-up would go under. Fortunately, on the side, the company had built up TripAdvisor.com as a demo site to show the prospective clients what a vertical search engine could do. When he saw TripAdvisor.com start to pick up traffic, he decided to pursue an online advertising based business model with banner ads. “Going B2C was daunting and not in our core DNA,” Kaufer remarked. But testing hypotheses was very much in the company's DNA, as well as evaluating data to learn and adjust. TripAdvisor, in effect, was a model lean start-up with an engineering-driven, product-focused founder.

After a few weeks of watching no click throughs, Kaufer executed his second pivot: a cost per click model (now known as CPC). Every time a consumer clicked on a hotel to book a room, TripAdvisor would charge the hotel something. Suddenly, everything began to (literally) click. Three months into launching the new model, TripAdvisor was earning $70k per month and achieved breakeven. The company has grown profitably ever since. Kaufer originally hired editors to comb the Web for great travel articles and link to them, and then allowed users to post their own reviews on the site as a whim. When the company saw that user reviews were getting all the traffic, they adjusted to focus on user reviews, such that fresh, authentic content was always available and didn’t cost the company any money to produce.

TripAdvisor And Expedia: From $4 million invested to $4 billion in value

With these adjustments, TripAdvisor grew rapidly and successfully. The company agreed to be acquired by Expedia/IAC in 2004 for $210 million in cash, a huge win for all, particularly given their amazing capital efficiency: they had only raised $4 million in venture capital. Under Expedia, TripAdvisor continued to flourish and grow – they would feature Expedia’s ads on their site and reap the revenue benefit when users clicked on those ads. Expedia grew to account for roughly one third of the company’s revenues. In December 2011, Expedia felt it wasn’t getting full economic credit for TripAdvisor buried within its financials and so spun TripAdvisor out as an independent company, where it now trades on the NASDAQ with a $4.8 billion market capitalization as of this writing.

Scaling Lesson 1: Focus On Finding A Great Business Model

After some searching, TripAdvisor found a magical business model, representing social media and user-generated content at its best. Content is free and supplied by consumers who write reviews voluntarily. These consumers allow this content and their own engagement to be monetized without asking for anything in return. Customer acquisition is driven mainly through natural search (the art of Search Engine Optimization, or SEO, was practically invented by TripAdvisor) thanks to the huge volume of great content (as Kaufer pointed out to me: “if a review comes on in Thai of a Bangkok hotel, suddenly it’s a better product”), long history and brilliant manipulation of Google’s search algorithm. Advertisers are brought to the site and driven mainly through self-service channels, so there is no need for a large sales force or account management team. As a result, gross margins are very high at 98% (not a typo!) and EBITDA margins are 47%. Think about that. For every dollar of revenue, the company is able to drop nearly half to the bottom line. I’m not sure the Mafia could do better. In the hyper-competitive world of technology and consumer Internet, it is hard to find a company that is pound for pound as profitable as TripAdvisor.

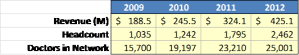

TripAdvisor is a classic example of a network effect business and a reminder of how financially attractive network effect businesses can become at scale. There are three sides to the network: the consumer, the venue and the advertiser. The network becomes more valuable as it grows to each party – with more consumers providing more interesting content, more venues providing more access to vacation options and more advertisers offering deals and convenient bookings. This virtuous cycle has fueled its growth nicely and allowed the company to drive very efficient value. The chart below shows their financial performance over the last few years, with forecasted 2012 revenue of $767M and EBITDA of $339M. At its current 20-25% revenue growth rate, TripAdvisor will join Akamai in the billion dollar revenue club in 2014. The $4.8B market cap is 6x revenue and 13x EBITDA, so not insane multiples on a comparable basis.

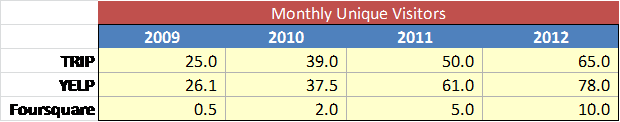

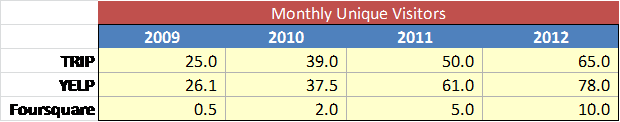

As a side bar, I thought it would be interesting to compare TripAdvisor’s Unit Economics with those of Yelp and foursquare. I took a few of the relevant metrics – unique visitors, revenue and market capitalization – and calculated a few ratios to demonstrate how good a job TripAdvisors does at monetizing their users. Here's unique visitors, with an estimate for foursquare based on some of their reported numbers:

As the chart below shows, TripAdvisor consistently achieves $12 annual revenue per user (ARPU) as compared to $1 for Yelp and unknown for foursquare.

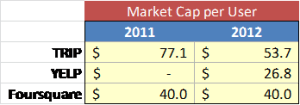

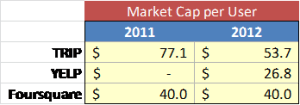

Yet on a market capitalization side, despite having a 12x advantage in monetization, the company is valued only 2x per user by Wall Street than Yelp and a mere 25% higher than foursquare, based on its most recent private financing round (reported to be somewhere north of $400 million pre-money). Amazing.

Scaling Lesson 2: Maintain a Sense of Urgency

Kaufer’s description of the TripAdvisor culture and development process makes it clear that he has been able to maintain a strong sense of urgency, even at scale. “No matter how large we are, I always want to maintain a startup mentality,” said Kaufer. "We have a once a week release cycle that we have religiously maintained for years…even with hundreds of developers working on a shared code base. If my team tells me they want to launch a new feature in two months, I ask them what prevents them from doing it in two weeks. Culturally, I’m happy to play the ‘crazy CEO who doesn’t get how hard it is to build and release stuff’ in order to push.” I know many CEOs who don’t have the same comfort pushing their engineering teams. I wonder if Kaufer’s ability is here is in part grounded in the fact that he himself was a vice president of engineering and feels comfortable challenging his product team with authority.

Scaling Lesson 3: Maintain a Product Focused Culture

Kaufer described to me that with his engineering roots, the company has always had a test and learn culture and a product-focused culture. “I enjoy focusing on building a great product,” he commented simply. “I can maintain that focus as we grow because I have a fantastic executive team who enjoys doing things that I don’t enjoy doing.” The company’s vice president of engineering posted a terrific blog about how the engineering culture has scaled and shared something with respect to the role of engineers that I thought particularly interesting: “We do not have ‘architects’ – at TripAdvisor, if you design something, your code it, and if you code it you test it. Engineers who do not like to go outside their comfort zone, or who feel certain work is "beneath" them will simply get in the way.” In other words, there is a certain style of developer required to fit into the TripAdvisor culture – someone who is focused on building great products end-to-end, just like the CEO is.

Scaling Lesson 4: Create Entrepreneurial Pockets

Kaufer described his technique for building entrepreneurial centers while scaling. “Any time you want to expand, you have the question – do you build it into the mother ship or acquire companies and keep things separate? I prefer to keep it separate and give it some CEO love. Whether its an internally built effort or something you incubate through an acquisition (we’ve acquired over a dozen companies), keep it separate operationally. Staff the team separately, give it attention but don’t let it get bogged down with the mother ship.” For example, one of the company’s divisions, FlipKey, is hiring engineers, just like other divisions within the company. He tells them to just go out and find the best engineers they can find and hire them without bogging them down in a centralized recruiting process that would clash with other divisions’ hiring.

Comparing TripAdvisor with Akamai

There are a few similarities to the TripAdvisor story as there are with the Akamai case study but some differences. TripAdvisor founder Stephen Kaufer is the classic technical founder who has grown with the company to be the end-to-end leader. Kaufer told me he always thought he’d be tapped out and replaced around 100 employees. With 1,300 employees and 12 years after its founding, he remains CEO of the company. Although Akamai’s founders were engineers, they hired Paul Sagan and George Conrades to run the company very early on. Sagan was thus almost like a cofounder and, similarly, has been with the company for 12 years. There is something powerful about that enduring focus – a leader who continues to grind away at driving improvements, results and managing scale over a long period of time. Neither leader was ever "exit" focused, but rather focused on building a great business that can endure.

TripAdvisor’s Future

TripAdvisor may have a magical business model, but consumer travel remains a very competitive market. Google’s $700M acquisition of Cambridge-based ITA and more recent acquisition of travel content leader, Frommer, is an indicator that others are in pursuit of TripAdvisor’s core business and juicy profit margins.

That said, whatever the future may bring, the lessons from TripAdvisor’s successful twelve year journey to scale are enduring.

Thanks to Stephen Kaufer for his help with this profile as well as Zach Ringer for his assistance with the research and analytics. For more on TripAdvisor’s business and strategic choices, see the Harvard Business School case written about the company.