I have been thinking lately about how hard it is to scale start-ups. The Lean Start-Up movement, as exemplified in Eric Ries' book The Lean Start-Up, has appropriately focused a great deal of attention on the hard decisions and techniques required to create a company from nothing. But once the company has honed in on a strong value proposition and found initial product-market fit, what is the best approach to scaling it? And what lessons can be applied to the early decisions you make as a start-up? After all, scaling is hard. Really hard.

To help shine some light on this topic, I’ve decided to do a series of blog posts of case studies of companies founded in the last 10-15 years that have made the transition from finding initial product-market fit to building a large, scalable, platform company. Facebook and Google would be obvious choices for this, but so much has been written about each of them and they represent such special business models, I worried that it would be both hard for entrepreneurs to relate and hard for me to develop new insights. So instead, I am picking a few companies with less well known stories that may resonate with today’s entrepreneurs. The first one I’ll focus on is Akamai.

Akamai: The Present

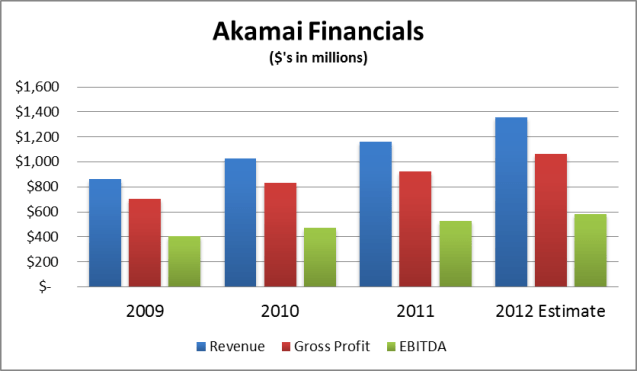

Many people know Akamai as the purveyor of the Internet’s backbone. Incorporated in 1998 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the company’s network of over 100,000 globally distributed servers provides an infrastructure layer that accelerates the distribution and delivery of content, media and applications. With over $1 billion in revenue, 2000 employees and a market capitalization of over $6 billion, Akamai has become a role model for scalable start-ups. The chart below shows the company’s strong financial performance from 2009 to the present. In 2012, analysts forecast the company will achieve nearly $1.5 billion in revenue, over $1 billion in gross profit and $500 million in EBITDA. I can't think of many companies founded in the same era outside of Google and Facebook with similar financial performance. How did Akamai do it?

Founding Akamai

Interestingly, the company’s founding vision was not a lean idea, but rather a big idea: to accelerate and manage Internet traffic on a global, highly scalable, highly distributed scale. Technical founders Tom Leighton and Danny Lewin built the original prototype at their lab at MIT starting in late 1996 before raising capital, so in a sense Akamai’s Minimum Viable Product (MVP) was a prototype with the basic architecture and traffic mapping in place that validated algorithms for the founders and investors alike. So the first interesting scaling take-away for me of the Akamai story is: they pursued a very big idea, but utilized lean principles in the sense of hypothesis-testing and avoiding waste. Later joined by Jonathan Seelig, an MIT Sloan MBA student, the Akamai team raised an $8 million Series A based on the lab prototype in order to commercialize the product. They didn’t raise their Series B until they proved some of the initial hypotheses around market adoption and were ready to scale the sales efforts, as described below.

Scaling Akamai – Part 1: A Little Fat

The company quickly realized that its initial commercial product was in huge demand – they had reached product-market fit nirvana. The first year of revenue (1999) was $4 million – a remarkable achievement. But the second year (2000) was simply astounding: nearly $90 million! Despite the Internet bubble bursting, the company was able to generate over $160 million in revenue in 2001. Akamai found itself truly inside the tornado. They raised a Akamai’s Series B of $20 million shortly after the Series A to fuel the growth.

Co-founder Seelig told me that they realized that they had gotten to that rare point where “the opportunity presented itself to go big” at the same time as the capital markets provided capital at a good valuation to support going big. Seelig described the frenzy inside the company to hire like mad (they had over 1000 employees by the end of 2000), to scale all aspects of the operations and team (experienced operators Paul Sagan and George Conrades were quickly hired to lead the company) and to address the initial product's warts. Seelig shared with me that these warts were in all the functional areas you don’t think to focus on building for scale in the early days – such as reporting, billing and administration. This presents the second interesting scaling take-away of the Akamai story: when you achieve product-market fit, it’s ok to have some waste in order to grow fast. If you find yourself in that privileged position, don’t be cautious. Go after it aggressively, even if it means risking making hiring and operating mistakes and wasting capital – so long as this capital is relatively cheap, as it was for Akamai in the midst of the Internet bubble. Look at the (quite ugly) P&L for Akamai in 1999 and 2000 – costly mistakes were made, but ultimately enabled the company to scale as rapidly as it did:

| ($'s in millions) | |||

| 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | |

| Revenue | $4.0 | $89.8 | $163.2 |

| Gross Profit | $(60) | $(886) | $(2,436) |

| EBITDA | $(56) | $(899) | $(2,414) |

| Market Cap | $23,184 | $3,165 | $536 |

| Head Count | 464 | 1,300 | 841 |

Looking at the numbers, it's obvious that 2001 was a dramatic year – the company had to cut back head count significantly as the market capitlalization plummeted from the highs of the IPO. Even more tragically, the company's founder, Danny Lewin, was killed on one of the 9/11 airplanes. The leadersihp team had to rally to overcome these two difficult blows and make difficult financial choices to recover. Akamai learned a scaling lesson that I've seen play out in typically less dramatic fashion, but nonetheless difficult: scaling is never a linear path. There are always set backs and speed bumps along the way to growth and greatness.

Scaling Akamai – Part 2: From Product to Platform

As the company’s first product offering – content acceleration – hit the tornado in 1999, they began working on transforming the company from a one-product success to a platform. Seelig told me that the founding vision always was that Akamai would build a global distribution platform, but the first application was static content from websites. In effect, this was the company’s MVP to prove out the core infrastructure. But once this first application took off, they began developing the suite of additional applications that form today’s behemoth – streaming media, dynamic page assembly, whole site assembly, e-commerce distribution, etc. Here the company was challenged to prove it could repeat its success with its first product. Systems were put in place and professional managers with experience in building mission-critical products were hired. This effort leads to the fourth interesting scaling take-away: Just because your first product is successful, it doesn’t mean you’re a product genius. Product geniuses are those that build rigorous product development processes that allow multiple successful products to be developed and marketed. This is the magic of what Akamai and other multi-product companies achieve as they scale. Without a repeatable product development process, they are doomed to be one-hit wonders.

Akamai Going Forward

There are a lot of challenges ahead for Akamai. The company faces competitive pressure that some analysts think will challenge their margins going forward and the stock has slumped recently from a high market capitalization of $8 billion to a “mere” $6 billion. CEO Paul Sagan has announced he is retiring after 13 years at the helm and the board will need to select a new leader for the company’s next phase. Whether Akamai turns into an even bigger platform company success story or not is still to be determined in the coming years, but there is no question that the company represents an amazing case study for students of the start-up game focused on scaling.

Special thanks to Jonathan Seelig for his insights and Zach Ringer for his assistance with the research and analytics behind this blog post. For more on Akamai’s founding story and business model, see the Harvard Business School case written about the company.