In May 1996, Open Market completed a successful IPO and more than doubled on the first day of trading, ending with a $1.2 billion market capitalization. We had recorded $1.8 million in revenue the year before.

If investors observing this extraordinary phenomenon in 1996 were to have concluded that the technology market was in the midst of an unsustainable bubble, they would not have been wrong. But if that observation led them to refrain from investing in the Internet sector, they would have missed one of the most stunning legal creations of wealth in history.

In 1997, a Charles River Ventures fund yielded a stunning 15x return, backing such superstars as Ciena, Vignette and Flycast. Matrix had a fund in 1998 that yielded an eye-popping 514+% IRR. The Internet bull market continued to run for four more years after the Open Market IPO, finally ending in the spring of 2000. The average venture capital fund raised between 1995 and 1997 returned more than 50% per year.

Amidst all the recent talk of boom vs. bubble, there is a hue and cry that the current environment may smack of 1999. But what if it’s actually more akin to 1996? What if the fundamentals are good enough to support four more years of insane behavior before the music stops and the natural business cycle correction settles in?

The chart below from this week’s Economist on unemployment made me pause and consider this question. As evidenced from the unemployment curve in the last economic cycle, these business cycles can often last 4-5 years. 2009 was the trough year of the most recent business cycle – and a deep trough at that. 2010 was a year of firming and climbing out of a hole, but the tepid IPO market and general macroeconomic malaise seemed to linger until late in the year (similar to how 1995 felt). 2011 is the first year where it feels like a real boom – much like 1996. Employment lags economic output and is an admittedly imperfect indicator, but if you continue the analogy, it may be that the next 4-5 year boom cycle lasts until 2015!

Consider the following:

- When bellwether players go public (such as Netscape in 1995), there is a massive rush of capital and companies that follow. Facebook will likely go public in 2012 and be valued in the $50-75 billion range. This IPO and others like it (e.g., Groupon, Zynga) will create tremendous liquid wealth for a number of people and institutions who will likely pour that wealth back into the start-up ecosystem. That liquidity flowing back into the start-up ecosystem will arguably fuel the boom.

- Macroeconomic choppiness is holding back more dramatic market euphoria. Tsunamis, Middle East crises, government shutdown threats and a looming budget deficit are all dampers on the market. But if some of these dampers clear out – if there is a period of reasonable international stability, if a divided US government can strike another fiscally responsible deal for the upcoming budget year and begin to deal with some of the long-term, fundamental drags on growth, then the markets will become even more euphoric. Remember, it wasn’t a straight line between 1995 and 2000 – there were a series of macroeconomic crises on the domestic front, such as a near government shutdown (sound familiar?) as well as international crises, including the Mexican debt default, Russian currency defaults and the Asian market crisis. Let’s not forget that Time Magazine featured Alan Greenspan, Rob Rubin and Larry Summers on the cover in February 1999 with the headline: “The Committee to Save the World.” At times, this period saw pretty grim macroeconomic trends, while the Internet continued to boom in the trenches.

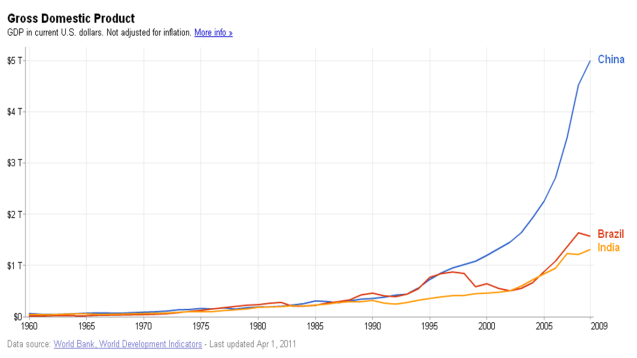

- Thanks to recent decades of strong growth, the combination of China, India and Brazil have GDPs that are 4x the size and impact on the global economy as compared to the 1990s (see chart below). Demand from these, now larger, economies are having a very positive effect on the US tech market. They are gobbling up mobile devices, PCs, routers and other technology gear at a rapid rate. This powerful source of economic demand didn't exist 15 years ago.

- All the existing technology players are awash in liquidity and all the numbers are bigger this time. There are eight US-based global technology companies with market capitalizations of greater than $100 billion (Apple, Google, Oracle, IBM, Microsoft, Intel, HP, Cisco). There are a handful of companies that are very well-positioned, growing fast and could be the next $100 billion players (Amazon, Dell, Netflix, EMC, VMWare, Salesforce.com and Baidu come to mind). These companies either didn’t exist in the mid-90s or are in infinitely stronger positions than they were 15 years ago. Internet usage, mobile phone usage, advertising dollar spend – all have grown enormously over the last 15 years to provide a stronger foundation underneath the latest boom. See the chart below, which will only explode further when updated for more recent figures that will take into account Internet access via mobile phones.

The point here isn’t to be Pollyannaish. I recognize that we have major structural issues in the global economy and they are perhaps more daunting than they have ever been. And the recent run up in the stock market has many arguing that the bull market won't last much longer. If oil soars to $150 per barrel, a few more soverign nations default on their debt obligations and gridlock persists in Washington, we could be looking at another recession as soon as 2012.

Yet, with entrepreneurship on the rise, with this generation of young people (“the Entrepreneur generation”) surging in their use and interest in technology and digital content, with some of the positive fundamental forces in innovation, it may just be that the music may not stop for another 4-5 years. Wouldn’t that be something?